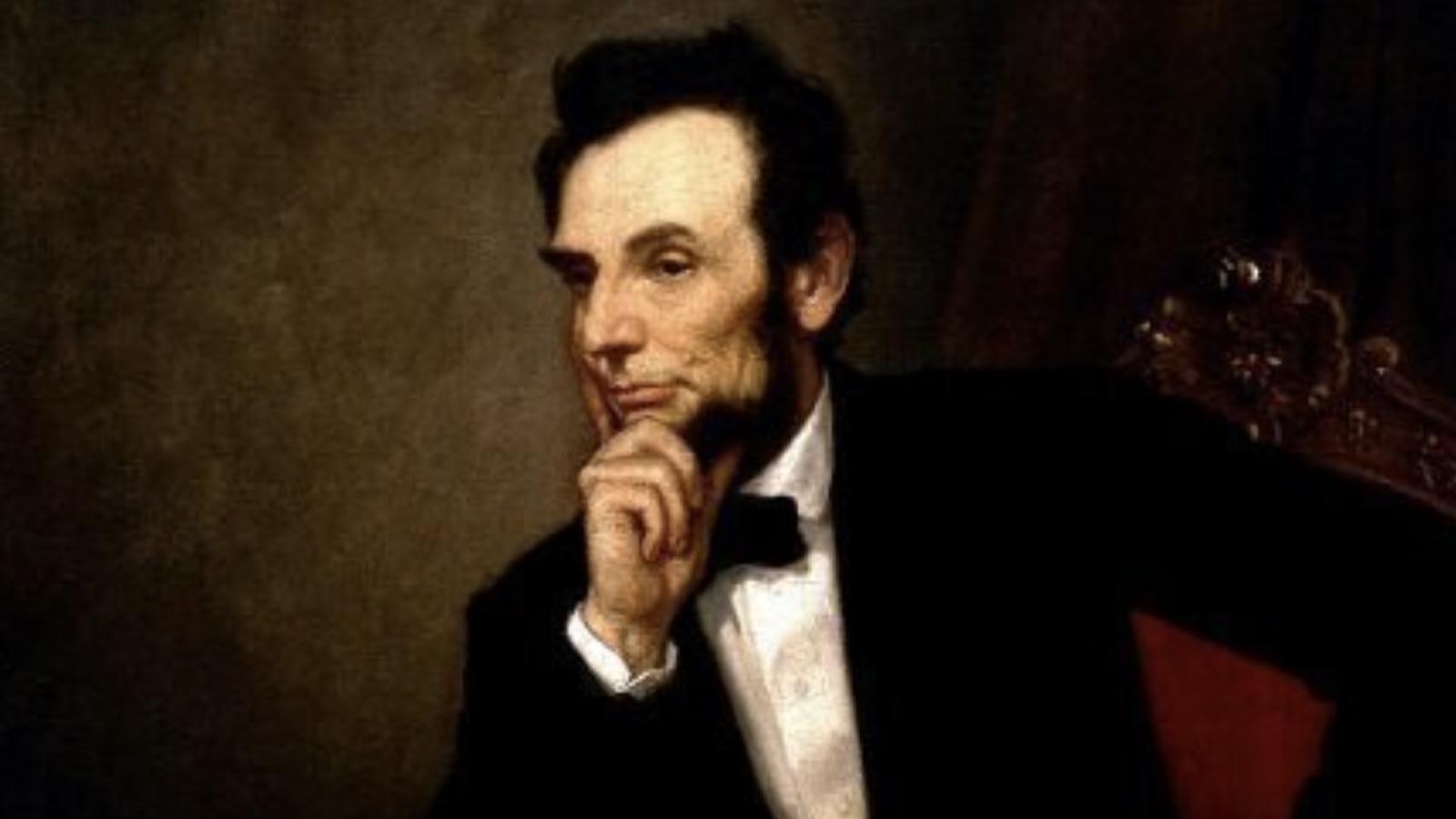

President Abraham Lincoln altered the course of the Civil War and American society when the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1863. But the Proclamation actually had its roots in a key announcement made on September 22, 1862.

In what became known as the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln made the threat clear, and in public, to the Confederate states that if they didn’t return to the Union by January 1, 1863, the President would make a proclamation freeing slaves in those rebellious territories.

Lincoln said that “on the first day of January . . . all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

He was also quick to cite that the Proclamation came under Lincoln’s executive powers in relation to the Constitution’s Commander-in-Chief Clause.

“I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States of America, and Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy thereof, do hereby proclaim and declare that hereafter, as heretofore, the war will be prosecuted for the object of practically restoring the constitutional relation between the United States, and each of the States, and the people thereof, in which States that relation is, or may be, suspended or disturbed,” he stated.

President Lincoln had given the states in rebellion about three months’ notice to lay down their arms and give up their desire for a separate nation.

Historian Harold Holzer detailed the debate within Lincoln’s cabinet over the preliminary Proclamation, which had been ongoing for about two months prior to the September 22, 1862 announcement.

Lincoln was persuaded by Secretary of State William Seward to wait until the Union had won a significant battlefield victory. The Union forces had just repulsed an attack by General Robert E. Lee’s forces at the Battle of Antietam, which Lincoln saw as the sign that the time had come for the Proclamation.

“I made a solemn vow with God that if General Lee was driven back . . . I would crown the result with a declaration of freedom for the slaves,” Lincoln told his cabinet members.

The Proclamation was controversial even in its preliminary form and it only freed slaves in the 10 rebellious states not controlled by Union forces, leaving slavery intact in four Union states where it was still legal and several other areas. Lincoln and his advisers understood that an act to free all slaves in the United States would be on shaky constitutional grounds and would most likely require a constitutional amendment.

The 10 states in rebellion as of September 22, 1862 had no intention of returning to the Union, and on January 1, 1863, Lincoln signed the final Emancipation that had several changes, including a provision that allowed freed slaves to fight in the Union army.

Both the preliminary and final proclamations were executive orders. They made the end of slavery one of the Union’s principle objectives of the war.

And what did the New York times say about this at the time?